Introducing my unconventional, creative & anything-but-linear job as a problem solver.

Hi there! Welcome to my little corner of the internet. I am a facilitator, a problem solver and the founder of She Consults. I guide and help organizations solve complex social problems. I approach problem solving using the design thinking process along with a side of curiosity, creativity and collaboration. I don’t do anything small; I believe the impossible is possible and I challenge my clients to think big too. The big problems deserve dedicated time and space under the microscope. My job is to create that space for clients to do the important work of solving the big problems of today. I craft and facilitate customized workshops and tools to empower clients as they work through the design thinking process. I am right by their side, acting as their problem-solving buddy.

“You are a facilitator and problem solver? What does that even mean?” I hear this so often, and four years ago I would have been asking myself the same question. What I do isn’t a traditional job, therefore people don’t always understand what it is I actually do, what a typical day looks like, what my work process is.

Hence, this blog post. Buckle in as I introduce you to my unconventional, creative and anything-but-linear process (because twisty turny paths are where all the learnings are, right?).

When a client first reaches out, they more often than not come to me with a vague idea of the problem they’re trying to solve. They are often concerned with the symptoms of the problem, and sometimes even unaware of what is causing the problem itself. A big piece of the process that I take teams through is digging deeper to uncover the root cause. Approaching the problem’s root cause ensures a higher level of success in implementing the solution and making sure it is adopted long term, in turn completely eliminating the symptoms the client initially came forward with and lowering the chances of the problem and its symptoms recurring. If we think of an iceberg, what we see above the surface is only a piece of the whole, but because we don’t see what’s underneath we don’t realize how big the iceberg actually is. We need to go below the surface—to truly understand the size of the issue—so that we can move forward with a full picture and understanding of all the angles and the magnitude of the problem.

Before I sit down to start designing workshops for a client, I need to familiarize myself with what the client is hoping to get at the end of the process, the proposed problem and any past key work that the team has done surrounding the problem in focus. I spend a lot of time prepping before the workshops even begin. I research the problem, watch videos, and read articles and studies. I listen to podcasts or talks from experts. I also try to understand what type of work has already been done by this team and others to solve the problem. I achieve this by talking with my clients and asking specific questions in addition to reading past project reports, funding applications and any other relevant documents. The final piece that I like to think about before designing a workshop for a client is, What is the goal of the workshop? What are they hoping to achieve? By deepening my understanding of the problem, historical work and desired goals for the workshop, I can then begin to design a path forward for my client.

Because more often than not, I am working with complex, systemic problems that have yet to be solved, there lives uncertainty: uncertainty about where to focus, uncertainty of roles and responsibilities of those around the table, uncertainty about which solutions to implement. The work is blanketed in uncertainty, and that is uncomfortable for us as humans, who crave the comfort of knowing, routine and linear, clear paths.

To combat the fears that arise from uncertainty, I try to support groups by aiding them in building a strong team foundation. I believe that anytime groups come together to tackle big problems, there should be work done on the front end to ensure the team is ready to move together, at the same pace, towards the same goal. But creating this alignment takes concentrated energy and time. Teams often skip this step, deeming it nonessential. But I argue that it is one of the most essential steps in shoring up the future success of a team, and ultimately their outputs, because team members can lean on each other when the fear of uncertainty creeps in, threatening to dismantle the work.

Thus, one of my first steps is to create and hold space for the essential team building work to happen. I have found over time that the secret to crafting the perfect environment conducive to problem solving and team building is to encourage creativity, collaboration and vulnerability.

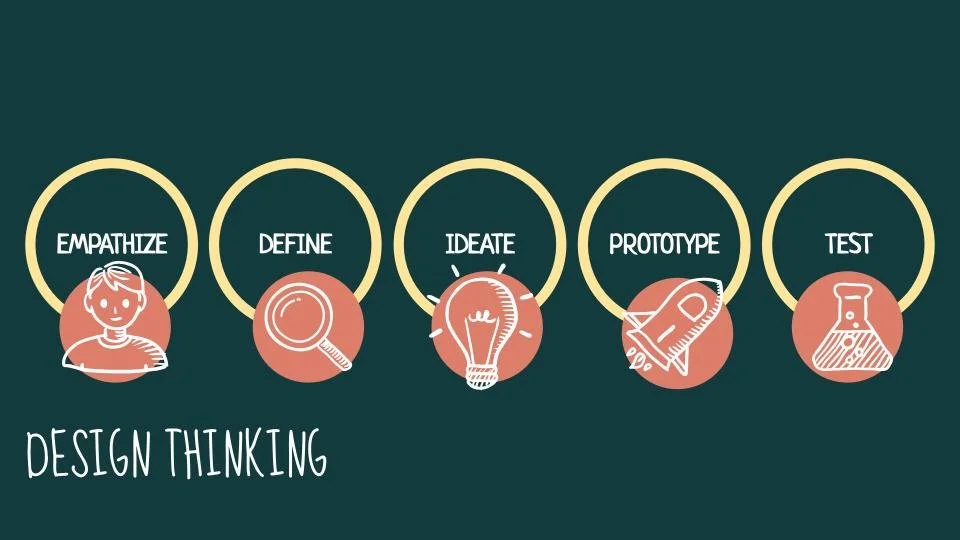

Once I sense that we are working from a solid foundation built on trust and centred on a mutual understanding and common goals, we’re able to dive in. At that point, I introduce a process called design thinking.

Design thinking is a process used to solve complex problems. A problem becomes complex when the path towards solving it seems convoluted and unclear. These problems have been unsolvable for a long time, centuries even, for a variety of reasons: ingrained and outdated mental models, systemic challenges, hurtful patterns and a lack of understanding of root causes.

Design thinking uses a human-centred approach that revolves around a deep interest in developing an understanding of the people who are the most impacted by the problem and with whom we’re designing the products or services.

Empathize: truly understand your user so that you can co-create meaningful solutions that support their needs, remove any barriers and/or challenges they face, amplify their hopes and minimize their fears.

Define: based on what you have gathered and learned about the user, apply a curiosity mindset and clearly define how you (and your team) might help the user solve a problem. The Empathize phase was all about understanding the user, while the Define phase is all about understanding the problem and how it impacts the user’s life.

Ideate: Now that the problem is clearly defined, which has provided direction, it’s time to explore possible solutions. This phase requires teams to refrain from judgement. No idea is off the table: even what might seem like a wildly outrageous idea may end up being a refined version of the final solution. We don’t want to limit our possibilities yet, and judgement does just that. By starting big and then narrowing, we ensure all ideas are explored and evaluated and the best possible solutions are picked to tackle the problem.

Prototype: Get your craft on. Pull out the construction paper, the glue sticks, the glitter and Lego: it’s time to build prototypes of your solutions. You don’t need to spend a lot of money or time to gather valuable feedback about your proposed solutions. Getting feedback early on in the process can make or break a project. If we open ourselves up to early feedback on a conceptual solution from the actual person whom the solution is designed for, then we can ensure that our solution’s intention aligns with the real needs of our user before we actually implement and spend tons of resources on a solution that doesn’t work. Prototypes allow us to test our ideas quickly, at small scale and low cost.

Test: Once the prototypes are built, it's time to gather feedback from the users. Does this help? Does this do what we intended? Is this sustainable? Take the feedback, integrate it into the next version of the solution, then gather more feedback. It’s a loop. This loop may seem tedious, but in the end, when you are ready to put real resources behind it, you can be confident it will be successful because you’ll have a fully fleshed out, user-tested and approved proof of concept.

The design thinking process is a guide to help a team move from problem identification to proven solutions. Within each phase of the process, there are tools and activities that are used to advance the team forward through the process. It is my job to select the appropriate tools, introduce and teach the tools, support teams as they use the tools and finally, capture and record whatever outputs and learning emerge from the tools. As a team moves through the design thinking process, I am taking the emerging data and learnings, recording it and presenting it back to the team constantly to ensure the next step is a progression of the learnings from the previous step. This record tells the story of the team and how they arrived at their proposed solutions. It also acts as a business case for those proposed solutions, to be used for work planning, funding applications, organizational restructuring, etc.

My expertise and official role ends once the team has gone through the entire design thinking process. I send the final report to my clients knowing that now that they have a set direction, they have the expertise and passion to go on towards implementing thoughtful solutions to big complex problems. I often stay linked to the project work even after I send that final email, because I become so invested in the team and the success of their solutions. My role shifts from process facilitator to cheerleader—cheering them on from the sidelines and offering additional support when and where I can.

My work days are never typical, because every problem is different, every team is different and these differences deserve and demand customized approaches and support. I thrive on this; the constant change challenges me to try things and to keep growing.

I am often confronted with concerns about timelines; there is an attached belief that to be innovative or tackle big problems in this way is time consuming and there isn’t time to spare because there are real people struggling right now. I have never been good at comforting those concerns, because they are right: there are often real, urgent needs that require immediate attention and action.

Let me try to comfort those fears here and now. I can confidently say that dedicated time and space allows for true, proactive problem solving that addresses root causes instead of just symptoms. But also, this proactive work can be done in parallel with meeting real and urgent needs. It doesn’t need to be either/or. We can fulfill current needs, like welcoming people needing a place to sleep into a shelter for the night, while also working towards creating a future where those needs don’t even exist and every person has access to their own warm and safe bed every single night forever.

This is my hope. The dreamer in me dreams of a world where communities and individuals are not only surviving, but thriving and flourishing. And the optimist in me believes I can play a small role in making that dream come true using design thinking.